Bellairs referencing this in college doesn’t really surprise us. Sumer Is Icumen In is an extremely old song (sometimes known as the Cuckoo Song, for reasons we shall soon see) dating to the mid-13th Century and was written in what’s now considered Middle English. Later in his senior year Bellairs reeled off a dozen or so lines of Chaucer's Prologue to the Canterbury Tales (in original Middle English, no less) during his national television debut on the G.E. College Quiz Bowl. There was no encore, per se, but we can sort of envision John, during the commercial break, leading the live audience in a rousing, free-wheeling version of the song (if only to mess with the mind of Quiz Bowl host, Allen Ludden. That's another story...).

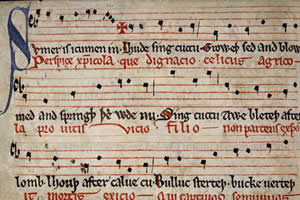

Anyway, this song is the earliest known four-part harmony song from Britain and was first written down at Reading Abbey in Berkshire in about 1240. The actual manuscript is now in the British Library but there is a tablet of stone in the ruins at Reading Abbey.

Sumer is icumen in (Summer has arrived)Carol Rumens, writing at The Guardian in 2011, notes the Russian belief that the number of times you hear a cuckoo's call represents the number of years you have left to live. “By asking the cuckoo never to stop, the singer may just be wishing that summer could be neverending. But it's plausible that there was once a similar, English superstition about the cuckoo, an interpretation that would heighten the final plea (‘Don't ever stop, now’) and give it added bittersweet flavour. Life, don't ever stop.”

Lhude sing cuccu! (Loudly sing, Cuckoo!)

Groweþ sed and bloweþ med (The seed grows and the meadow blooms)

And springþ þe wde nu (And the wood springs anew)

Sing cuccu! ( Sing, Cuckoo!)

Awe bleteþ after lomb (The ewe bleats after the lamb)

Lhouþ after calue cu. (The cow lows after the calf.)

1 comment:

My familiarity with this song is due to Patricia MacLachlan's use of it in her novel, Sarah, Plain and Tall.

Post a Comment